Basic statistical terms and concepts¶

In the lesson for this week we will be dealing with geochronological data, ages of geological material. These ages can be measured in many ways, but often several minerals are dated from the same sample to try to reduce the geological uncertainty in the measured ages. Even with extremely precise dating methods and excellent equipment, ages measured in geological materials are often quite variable owing to factor such as zoning of parent isotopes in minerals, partial loss of daughter isotopes, radiactive mineral inclusions, etc. Before we can consider any of these factors, however, we’ll need to understand some of the most basic statistical concepts.

Populations and samples¶

For any kind of analysis one might perform on geological materials, we collect a sample. The sample or sampling unit is material collected that is a subset of a much larger population. The population is the total number of occurrences of a particular thing in a defined area, and something that is not possible for us to access geologically. Consider an example of trying to date even a small igneous intrusion. Of the total volume of the intrusion, only a tiny fraction is likely to be exposed at the Earth’s surface. Moreover, of the accessible part of the intrusion, we are likely to only date 10-100 minerals out of the total number present in the intrusion, which could easily be millions or more. Even if we opt to use deep boreholes to access parts of rock layers not exposed at the surface, the volume of material sampled by the drill core is miniscule. Thus, our goal is not to try to access a population, but rather to collect a sample that is representative of the population.

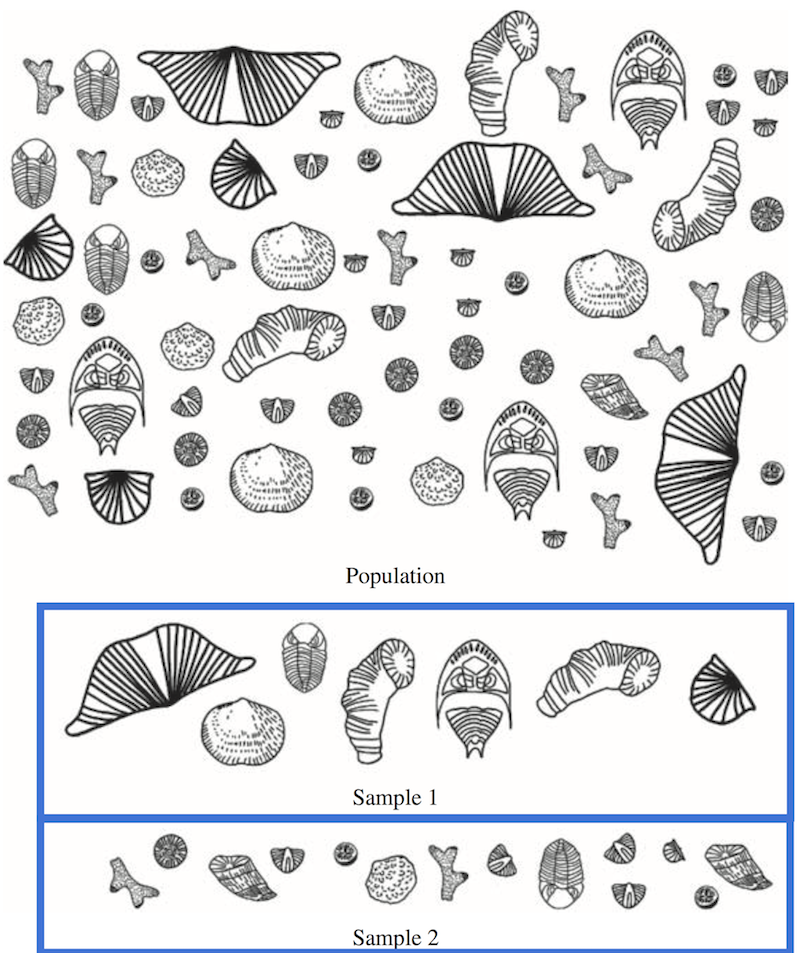

A representative sample is a sample that can be used to infer the characteristics of the population. In other words, the sampled material represents the main features (i.e., ages, fracture orientations, mineral assemblages, etc.) of the much larger population. Our goal as geoscientists is then to try to collect such a sample by collecting sampling units at random. The trouble is, a random sample does not guarantee the sample is a representative sample (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Two non-representative random samples from a population. Sample 1 (upper blue box) comprises mainly large fossils, while the fossils in sample 2 (lower blue box) are mainly small. Both samples were randomly selected from the population, but are not representative. Source: Figure 1.1 from McKillup and Dyar, 2010.

In Figure 1, the problem is that random samples collected from the same population may be very different from one another. In this case, the two random samples have very different sizes of the sampled fossils.

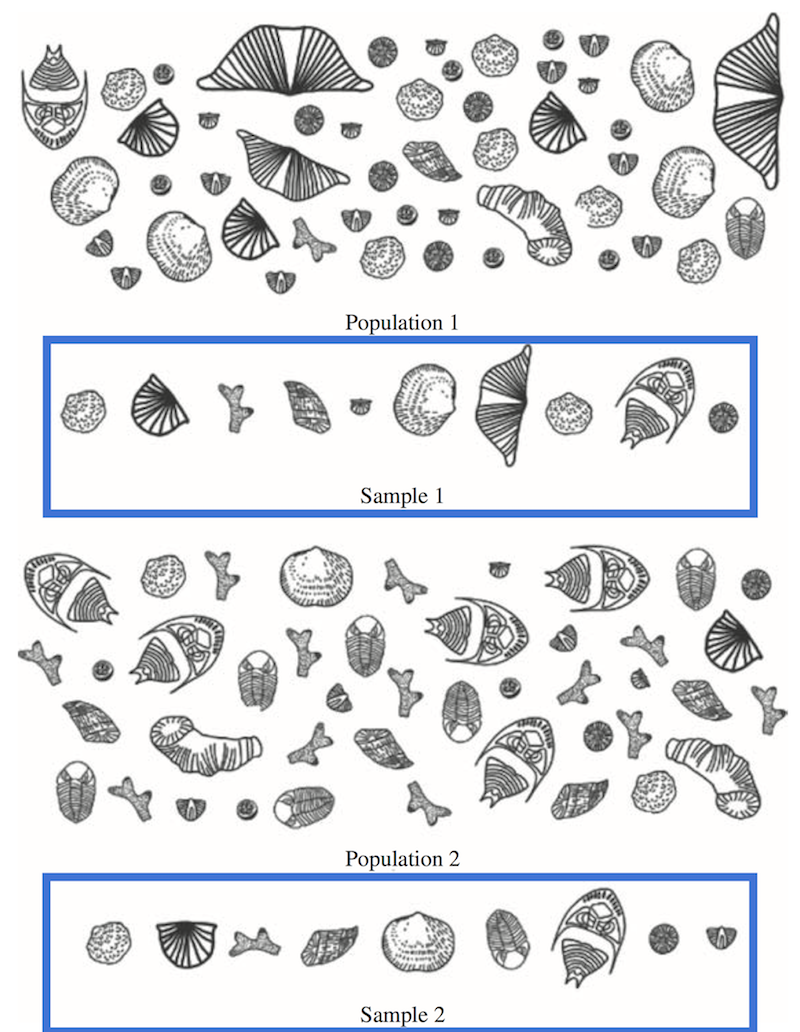

Figure 2. Two similar random samples collected from different populations. Here, sample 1 (upper blue box) and sample 2 (lower blue box) are similar, in spite of having been collected from different populations. Source: Figure 1.2 from McKillup and Dyar, 2010.

The problem in Figure 2 is that random samples taken from different populations may be quite similar. With the message from Figures 1 and 2, it should be clear that collecting a representative sample is difficult, particularly since the material available to sample for most geological cases precludes taking truly random samples.